Bonus Old Story: “New Flames for an Old Love”

You could call this post “Old Ideas for a New Tale”, because what I’m going to talk about is a story that turns 21 this year, yet contains the seed for the ending of my latest novel. There will be SPOILERS for the conclusion of Crashland (aka Crash in Australia), so if you haven’t read that yet but intend to I’d advise holding off. The story itself starts after this short preface.

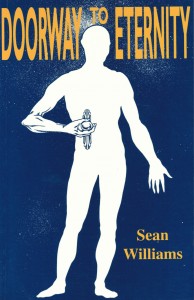

“New Flames for an Old Love” was my first published d-mat story. Not only that, but it appeared in my very first book, a small-press collection called Doorway to Eternity. Now long out of print, Doorway contained a spin on the traditional haunted house story (“Reluctant Misty and the House on Burden Street”, in which the house itself is the haunter), a weird novella about multi-dimensional stalking (the title story, inspired by The X-Files), and this story, which gave an origin for d-mat that hasn’t “stuck” in the universe of Twinmaker. But the ending did.

“New Flames for an Old Love” was my first published d-mat story. Not only that, but it appeared in my very first book, a small-press collection called Doorway to Eternity. Now long out of print, Doorway contained a spin on the traditional haunted house story (“Reluctant Misty and the House on Burden Street”, in which the house itself is the haunter), a weird novella about multi-dimensional stalking (the title story, inspired by The X-Files), and this story, which gave an origin for d-mat that hasn’t “stuck” in the universe of Twinmaker. But the ending did.

Matter transmitters had been used as weapons many times before I came along. A. E. Van Vogt’s “Secret Unattainable” from 1942 is a good example, in which a Nazi super-weapon goes wrong (and thank goodness it did). Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Disintegration Machine” got there first of all, in 1929. and this is what Sir Arthur had to say on the subject:

“I need not enlarge upon the revolutionary character of such an invention, nor of its extreme importance as a potential weapon of war. A force which could disintegrate a battleship, or turn a battalion . . . into a collection of atoms, would dominate the world.”

So there’s a long and fine tradition of using d-mat as a weapon. I didn’t know this at the time I wrote the story (in 1992). I just thought it would be very, very nasty if someone used d-mat to hack the matter a traveler is made of, not to turn them into a fly or whatever, but to reduce them to energy, destroying them (and potentially a large number of other things) in the process. Such a WMD could knock humanity back to the stone age if applied injudiciously. Which is what happens in this story . . . and in Crashland.

“New Flames” is an early story, and revising it brought back a lot of memories. Normally I write stories from start to finish. This one, though, I didn’t: the first scene I wrote was the “dissolve” right at the end. I remember it was very late at night and I wanted to get that scene down before going to bed. The next morning, I got up and wrote the rest. Finding a home for it certainly encouraged me to write more in this vein.

The world of “New Flames” doesn’t quite map onto either Twinmaker’s or The Resurrected Man’s. Marcus deBarrow is never referred to again, and “D-mat” quickly becomes “d-mat”. If you’ve read Crashland and you read this story you’ll see that I changed a lot of the details–including the phrase “loose gluons”, although I’m not sure if “unstable matter” makes any more sense. But I always wanted to use that big ending somewhere, and now I have.

I hope you enjoy this little glimpse of d-mat as it used to be.

“New Flames For An Old Love”

From the ridge it doesn’t look so bad. i stand with my back to the rising sun with the wind whipping at my sunburnt skin like fingers of felt, and watch the Djaralinga Range slowly change colour from deep brown, to purple, to orange and lastly to ochre. The mountains are ancient and worn, cut by weather into twisted, bulbous faces. The wind gives their empty mouths a voice I can almost hear.

From the ridge it doesn’t look so bad. i stand with my back to the rising sun with the wind whipping at my sunburnt skin like fingers of felt, and watch the Djaralinga Range slowly change colour from deep brown, to purple, to orange and lastly to ochre. The mountains are ancient and worn, cut by weather into twisted, bulbous faces. The wind gives their empty mouths a voice I can almost hear.

Below me, in the valley, the Hotel is gone. Where once stood a teeming mini-metropolis—home to fifty-odd staff and three hundred guests—there is now…simply nothing. Tremendous gashes in the soil resemble open graves where the foundations once lay. The main swimming pool has become a muddy hole that gapes at me like an empty eye socket. Even the surfaces of paths and narrow roadways have disappeared, leaving the reddish dirt oddly scarred, as though a passing giant from the Dreamtime once carved strange hieroglyphs here and then moved on.

Last night, I scrambled through the dust and dirt looking for remains—or anything at all—but found only some clothes I brought here months ago, a battery-operated radio and the pistol I kept in a draw in my desk. The latter I find grimly amusing: the desk itself has gone, but the pistol remains.

In the face of the overwhelming loss surrounding me, this small mystery quickly pales into insignificance.

My world is dead, and I will be too, before long. The Hotel pumped water by electricity from the water-table below the desert up half a mile of narrow, twisting pipe, but the generator that powered the process has gone with the rest. I have no food and, with the Network down, no way to leave. There is a small airstrip a few miles from here, where the first of the D-mat capsules were off-loaded, but no planes.

So I sit and watch the sky, waiting.

#

Shelley: blonde hair, tanned skin, green eyes, a small mole below her right breast. Passionate and kind, concerned about others and willing to fight for what she believed was right. Where I was passive, she was active; I dark, and she light. We supplemented each other perfectly; anything one lacked, the other provided.

Shelley and I also had a lot in common, including similar tastes in food and friends. Although one of the latter was Marcus deBarrow, an old school-mate of mine and Shelley’s ex-lover, we rarely talked about him; there were more immediate things demanding our attention than the past. He only became an issue the night she saw him for the last time, six months before she and I were married.

dB and I had attended the same high school in Adelaide. Recent photos show him to be unchanged since then: still tall, strong, yellow-blonde and awkward-looking. I can’t say that we were close because I don’t think he was ever close to anyone—and I certainly didn’t know him very well, as history has demonstrated—but we called each other friend. That counted for something, then.

In retrospect, I find it amazing that I had no inkling of what was to come. I knew he was bright—perhaps even brilliant—and sullen at times, but I never once guessed that he had the potential within him to change the world.

As the years flew by, he and I drifted apart. While I left Uni to concentrate on work, he passed Honours. I became a chef; he started his Masters. I took control of my first restaurant; he completed a PhD thesis. The last time I saw him, he had finally left university and was wondering what to do with the rest of his life. Five companies had offered him employment in related fields, none of which really had anything to do with his real work, and he had turned them all down. He was so far ahead of his time that he himself doubted he would find suitable work for the next twenty years, except under tenure. But he didn’t want that, either.

It was about then that he went on a cruise to save some whales from the Japanese ocean fleets, and met Shelley.

“He’d been on a conservation trip most of his life,” Shelley explained when I first met her, “which is unusual for a scientist. I was working for Greenpeace, on the boat, and he was just this guy who gave The Cause some weight by being highly qualified, you know? It didn’t matter that he was a quantum physicist, not a marine biologist. He had a PhD, and that alone was enough to impress the media.

“Anyway, we started talking one night—about life and everything, the way you do out at sea—and he opened up. Did you know his father was killed by a chemical spill, back in the eighties?”

I shook my head. This side of his character was new to me. “That’s what made him join the Greenies?”

“I guess so. To get his own back, maybe.” She shrugged. “dB was lonely and mixed up and grateful for someone to talk to. He was passionate about a lot of things, including the environment and all that—really angry at times. He wouldn’t have been on the boat if he wasn’t, I guess. He said that the Earth’s survival depended on the reduction of three things: population, energy-consumption and big business. People want goods and services; business burns fuel and squanders resources in order to supply demand; people get used to what they have and want more; big business encourages this attitude because it increases demand and makes them rich; and so on, with the environment crushed in the middle. It really made him mad, the irresponsibility of it all. He wished there was something he could do to help, but, for all his brains, he didn’t know what.

“I felt sorry for him, and that’s how it all started.”

After the trip—which ended in an ‘amicable’ confrontation with the Japanese Navy—they started seeing more of each other. Six months later, they moved in together. He wrote papers for academic publications while teaching part-time at the Free University; she contributed the main part of their joint income from her promotions work with Greenpeace.

They continued that way—not really going anywhere—for almost two years, until she came home one day to find him in the bedroom, packing clothes into two large suitcases.

“I’m going to America,” he said. “Something’s come up. A chance to do some real work.”

“What? Who with?”

“QDos, in Dallas.” He pronounced it ‘kudos’. “They rang this morning. I leave tomorrow.”

“Wait, hold on a minute. How did they know about you? Through your papers?”

“No. I wrote to them.”

“You didn’t tell me anything about this.”

“I wasn’t expecting them to reply. It wouldn’t have mattered if they hadn’t, would it? I sent them an idea—”

“Just like that?” Her sarcasm was biting but he didn’t even notice.

“—and they offered me a job. Or, at least, the chance to see if my idea will work.”

“How much are they paying?” She was so stunned to see him taking the initiative her mind refused to function on anything but a purely material level.

“One million dollars.”

She blinked. “For how long?”

“Six months. And that’s just a retainer, not for the patent. I’ll keep that until they decide they want to buy it.”

She sat down on the bed. “Jesus…”

He sat next to her and took her hand. “It might not work out, Shell.”

“Then they’ve paid a hell of a lot of cash for just an idea, haven’t they?”

“It’s a big idea. The biggest. If it works—” He shrugged. “If it works, then I’ll be set for life. Everyone will.”

He rose and continued packing. She started to cry. He was happy; for the first time, he was truly happy. She could see it in his face. It hurt her a lot that he hadn’t asked her to go with him.

He left the next day. A week later he sent a cheque to cover his share of the rent. Then he sent her a lump sum to cover him for three months, with a short note to apologise for not writing or ringing. He was too busy. A courier arrived to collect the rest of his personal belongings.

She returned the cheque with the crates of clothes and notes, and found another apartment. She forwarded her new address, but still heard nothing. Shortly thereafter, she quit Greenpeace to work for an advertising firm.

Then she met me.

I was running a four-star establishment in Melbourne, and the company she worked for handled our account. We ‘did lunch’ a few times, then dinner, then fell in love. The fact that I worked nights and she days might have killed another relationship, but only enhanced ours. From the very beginning, it felt right for both of us—as though we had been destined to be together all along.

“I don’t think we ever really loved each other,” she once said of her years with dB. “He was just a way of filling time, to keep me busy until I met you.”

Time passed smoothly. We dreamed of starting a business of our own one day, somewhere. I had been saving for ten years and had amassed quite a tidy sum; it wasn’t long before she began supplementing that pot of gold from her own income. When her father died and left her in excess of four hundred thousand dollars, that went into the kitty too, tied up in investments. We moved to Sydney and decided to get married.

Four years after she split up with dB, six months before our wedding, she received the phone call. His voice, she said, was thin from the satellite link-up, but breathlessly excited.

“I’m doing something at last,” he said. “In fact, I’ve done something. It’s ready. You’ll learn about it by the end of the year. Everyone will.”

“What are you talking about, dB?”

“I have to meet you for dinner,” he said. “You’re in Sydney, now? God, was it hard tracking you down! How about the Hyatt? That’s where I’ll be staying.”

She almost suggested the Hilton, where I was manager, but caught herself in time. She received the distinct impression this was a private thing. “Okay.”

“Great. I’ll be there soon. Ring you then.”

Three days later he rang her at work and arranged a time. She told me about it, of course, and confessed that she was nervous.

“Of what?” I asked.

“Of the way he sounds. He’s the same as he was back then—still mixed up, still angry…”

“Are you worried he might try to hurt you?”

“No, not really, but…”

She arrived on time and waited at the table for him to turn up. He was late, as usual. When he eventually appeared, he looked as though he’d come fresh from one of the upper-floor suites: black suit, new haircut, expensive cologne.

“Jesus, Shell, it’s been ages,” he said, swinging into the seat opposite her, all elbows and knees.

“Hi, dB.”

“And Sydney hasn’t changed a bit. Still full of cars and people and shit.”

“You haven’t been back?”

“A couple of times, on business. Didn’t have time to look you up, I’m sorry. Don’t have time for much, these days.”

She asked him what he’d been doing, but he evaded the question.

“Are you seeing anyone at the moment?” he asked.

She hesitated, then said: “Yes. I am.”

“Oh.” His face fell, but recovered quickly. “Hope he’s not jealous about the old flame being back in town?”

“No. He’s not.” She didn’t mention my name—not then, and not ever.

“Good.” He pulled the menu onto his lap and ordered for both of them. Nothing but the best, Shelley said, and he hadn’t forgotten that she loved lobster. The wine cost over two hundred dollars per bottle.

“This is a special occasion,” he said when she protested the cost. “The first chance I’ve had to celebrate. And I’m paying, so why not?”

He let it slip during dinner that he was not just wealthy, but rich. Despite his ideological hatred of planes, he had flown into Tullamarine Airport behind the controls of his own private jet.

“Couldn’t afford a pilot?” she joked.

“A hundred pilots—pfft!” He waved a hand dismissively. “I could buy the RAAF if I wanted to. They’ll be going cheap before long.”

“Why?”

“Can’t tell.” He winked. “That would be insider trading.”

Dinner over, they ordered coffee and his mood became more relaxed. The lights dimmed and he started to open up. His big idea of five years ago had not just worked, it seemed, but worked beyond all expectations. He wouldn’t tell her any details, just that it was ‘huge’. QDos, the company he still worked for, would rule the world within the decade, he said, financially if not politically.

“There’s a difference?” she commented.

“You haven’t changed either,” he said, smiling wryly. “The same old Shell, still trying to buck the system.”

“Not any more. I’m part of it, now.”

“Fighting from within?”

“No, dB. All the old anger is gone; I’ve grown up, see?”

“I wish I could say the same. The more I travel, the more I hate the system: the rape, the pillage, the mindless destruction of the Earth in the name of Profit. The middle class is worse than the Vikings, and it breeds faster too. It’s disgusting.”

“But things are getting better, surely? Recycling’s a way of life now, and people are changing—”

“Crap. People are as stupid now as they ever were. Anyone who believes otherwise is a fucking idiot.”

The outburst surprised her. She sat in silence for a moment, embarassed, watching him fume to himself.

Then he reached into his pocket and took out a flat, rectangular package wrapped in paper, which he juggled with one hand for a moment, as though uncertain what to do with it. She told me later that she half-expected it to contain a ring, and was terrified by the thought that he was about to propose to her. Not that she would have said yes. She simply didn’t know how he would handle the rejection.

He eventually gave her the package and nodded that she should open it. It contained a small gold pendant, as large as a five dollar coin and half again as thick. The chain was twenty-four carat gold and looked more valuable than the pendant itself, which was a flat circle, unadorned. There wasn’t even an inscription.

“dB, I—”

“Take it, Shell,” he said. His mask slipped aside for a moment, and she glimpsed the confused young man she had met on the deck of the Fight For Life seven years earlier. “I want you to have it.”

“I can’t, really, it’s—”

“Too much? Beyond price, if you want to know the truth, although it doesn’t look it. I had it made especially for you.”

“Why?”

“I don’t know for sure.” He blushed. “But when I look back over my work of the last few years, I don’t see much that’s human. It’s all biochips, quantum algorithms, ghost particles and shit like that. Nothing I can point to and say, ‘This has meaning. This is what my life is all about.’ You know?” He stared down into his open palms, avoiding her eyes.

“I treated you badly, Shell, when you gave me so much. I must’ve driven you crazy. But I think I loved you, in my way. I know how corny that sounds, but it’s true. You’re the only girl I’ve ever slept with, and I guess… I guess that counts for something. If you really don’t want it…”

She shook her head. “No, dB, I’ll take it if you want me to.” She cursed the words as soon as she said them. “Shit, that sounds patronising. I’m sorry. Thank you. I’ll always wear it.”

He blinked, and the new dB was back. The mask, the high-flying act. “Good. Will you promise me?”

“What?”

“That you’ll always wear it, of course. Or was that just a handy turn of phrase?”

“No.” She smiled openly; he was trying to crack a joke, something he was never very good at. “I really will.”

“If not on you, then at least with you. In a handbag or something, okay?”

“Yes, dB.”

“Just promise me one more time. You won’t go anywhere without it?” Not joking anymore.

“Okay, okay, I promise.” She mock-scowled at him. “Jeez, dB, anyone’d think you’ve given me the keys to the Sistine Chapel.”

“In a way, I might have, although that remains to be seen.” He leaned back into his chair and put his hands on his stomach. “Whew. Great dinner, wasn’t it? Another coffee?”

#

Later that night, as we lay together in our bed, we talked it all through. She was worried by something but couldn’t put her finger on it. Although unable to help, I wanted to try. Anything, if it made her relax.

Just as I thought she’d finally drifted off to sleep, she mumbled something into my shoulder that I didn’t quite catch.

“What?”

“I want you to have it,” she said.

“Have what?”

“The necklace.”

“Why?”

“I don’t know. Will ‘just because’ do?”

I levered myself up onto an elbow and studied her face. The pale moonlight drifting through the window barely sketched her outline, but I knew that she was frowning. dB had rattled her deeper than she would admit.

“Are you afraid of it? That it might be dangerous?”

“Like a bomb? No, I’m not. It just…doesn’t feel right, I guess. And besides, it doesn’t really suit me. It looks more like a man’s pendant.”

“Vanity,” I chuckled, stroking her face.

She bit my finger. “Please?”

“Okay,” I said. “I’ll wear the damn thing, if you want. But not on a chain. Maybe a bracelet, or something.”

“Thanks.” She kissed me and slid her hands around my neck. When they slid lower, they left an unfamiliar trickle of cold metal in their wake. As simple as that.

“So how does it feel to break a solemn vow?” I asked.

“I haven’t broken it.”

“Oh?”

“I said I’d have it with me all the time, and I will.”

“I see.”

“Yes. You don’t think you’re getting away from me that easily, do you?”

#

Three months after our honeymoon, Shelley was reading the morning paper while I made breakfast. Toast and coffee; nothing complex in a chef’s kitchen. I heard her mumble, “Oh my God,” and went to see what the matter was.

She waved the paper urgently. “This is it! This is what he was talking about!”

“What? Who?”

“dB! This!” She pointed at the article she had been reading, and I bent down to look. My eyes widened as I read, and I knew she was right. I knew it instinctively. His name wasn’t mentioned anywhere, but only dB could have done this. Besides, QDos was highlighted all the way through.

The headline screamed: A Revolution In Transport!

D‑mat had arrived at last.

#

The first capsules were up and running within six months, in most of the major capital cities that could could afford them. Although the article had foreseen cheap, instantaneous travel for everyone, D-mat initially failed on both counts. A jump cost two thousand dollars and took two hours; each capsule could process only twelve passengers in a full day, not counting luggage.

But those two hours and two thousand dollars could take you anywhere in the world—Moscow, New York, London, or Beijing, anywhere with a receiving station—without flying the space in between and without any sensation of time passing.

A year later, the second generation of capsules arrived. Half as expensive and twice as fast as the first, they were beamed directly from the QDos manufacturing plant to each receiving station. Not one of the delicate components arrived damaged: a convincing demonstration of the process’ efficiency.

The world was changing, and it was changing fast.

Most people were slow to realise, but I saw the possibilities immediately and pulled our investments out of cold-storage. I began searching for a site on which to build, and eventually chose the Djaralinga Range in the far north of Western Australia. The scenery was breathtaking, beyond belief. Ayers Rock was just a boring pebble in comparison. I started looking for investors who would be prepared to take the trip, and found two.

Shelley and I took them by D-mat to Perth, by chartered plane to the nearest landing-strip, and by four-wheel drive to the proposed site. The trip as a whole took three days, two thirds of which were spent behind the wheel of a Range Rover along unsealed ‘roads’. We had to hike the last four kilometres on foot.

It was worth it. They signed on the spot.

The fourth generation arrived the same month construction commenced. Four hundred dollars one way, twenty minutes duration, six hundred passengers per day per capsule. We installed industrial-sized receivers on the site, beamed the signals up to the satellite array, and thus saved thousands of dollars in transport costs. We imported concrete, wood, nails, water, food—everything—via D-mat.

People were starting to catch on.

When the Hotel Djaralinga officially opened, we were the second to offer scenery previously inaccessable to the public. The first was high in the Himalayas. The third was deep in one of the Atlantic trenches, where bizarre sea-life abounded, attracted by the lights. Someone even proposed opening business in low Earth-orbit. NASA was already using D-mat to beam astronauts into space, rather than sending them up by shuttle.

The fifth generation arrived—and this was the final nail in the coffin of the commercial air-carriers. Anywhere in the world for just two hundred and fifty dollars and ten minutes of your life. The Earth Network was established, with its headquarters in geosynchronous orbit above the equator, zero degrees longitude. Over a billion transmits were recorded in the first month of operation as humanity explored its new toy.

We had seven thousand guests in our first year. The next, we had almost seventeen thousand, and added extensions. We were heading for thirty-five thousand when D-mat announced that the sixth generation had been delayed by unexpected design difficulties. The cost would remain fixed for at least three years.

But that didn’t concern me. I was half-owner of one of the greatest lucky strikes in history. What did it matter if QDos decided to rake in a bit more money before the price inevitably dropped? Competition would form before long, I predicted; the small problem of design patents wouldn’t keep them at bay forever. I had half-expected Boeing or one of the other aerospace industries to have already released an alternate, and cheaper, version of the QDos D-mat. For the moment at least, QDos had a stranglehold on the market, and I couldn’t blame them for wanting to capitalise on that fact.

My thoughts and thanks occasionally went to dB, wherever he was, and whatever he was doing. I owed much of my happiness to him.

The Hotel was basking in success. I was still in love with my wife, and Shelley was still in love with me. The future looked bright, and I was ready for it.

Or so I thought.

#

The call came through at four in the afternoon. Shelley took it in her office and buzzed me as soon as she had hung up.

“I need to talk to you,” she said.

“Come on over, then. I’ll clear us some time.” Sensing that something was bothering her, I locked all incoming calls out of my work-station and instructed my secretary to deflect inquiries for as long as possible.

Shelley kissed me lightly as she entered the room and took a seat opposite the desk. She was frowning.

“What’s wrong?” I asked.

“I just had a phone call,” she said.

“And?”

“It was dB.”

That stopped me. I couldn’t imagine why he would ring after so many years. “What did he say?”

“Not much; he didn’t have long. But I asked him whether he was Mister D-mat, and he said yes, he was.”

“We knew that already.” It made sense. D‑mat had killed the planes, which he would have liked.

“But he said he was, as though he wasn’t anymore.”

“So?”

“Apparently QDos is holding onto the next generation, just like you thought. The prototypes are in a warehouse somewhere, ready for production, and cheap enough to wipe out cars forever. QDos could kill OPEC tomorrow if it wanted to, but it won’t.”

I imagined deals sweated out behind closed doors, greasy golden handshakes between faceless, powerful men. “dB doesn’t like that, I’ll bet.”

“Not one bit. He’s furious. He said that QDos is a malign tumor, letting the host die when it has the power to save it.”

“So what’s he going to do? Sell out?”

“I don’t know. He didn’t say.”

“What else did he say, then?”

“Not much. He asked me if I still had the necklace, and I said I did.”

I glanced guiltily down at my wrist, where the pendant hung from its golden chain. I had never removed it. The indirect honouring of Shelley’s promise had become a habit.

“True enough, I guess.”

“That’s not all,” she continued. “He’s coming here to see me.”

“When?”

“The day after tomorrow.”

“Why?”

“I…don’t really know. He was in a hurry. I could hear people shouting at him in the background. He said something about ‘loose gluons’ and ‘be ready’, and hung up.”

“Loose gluons?”

“I didn’t understand that either.” She shrugged. “He might have been talking to someone else.”

I got up from my chair, paced across the room to the bar and poured myself a Scotch. “Do you want him here, Shelley?”

“No, but I don’t want him not to come either. He’s an old friend, after all. If he does anything stupid I can just ask him to leave.”

“We could shut down the D-mats for a day, if you like. Keep him out.”

“It wouldn’t work. He’s not coming by D-mat. He’s flying in.”

“He’s what?”

“Flying. I guess he’ll want to land on the old air strip, the one we used to ferry in the first capsule.”

“God knows what sort of condition it’s in.”

She shrugged.

“What do you think, Shelley? Be honest.”

“I don’t want him here, but I don’t want to stop him coming. That’s what it boils down to, in a nutshell.”

“Okay. So we’ll make him a paying guest and maybe he’ll take the hint. No free holiday, if that’s what he’s after.”

“I don’t think that’s what he’s after at all.”

“Do you think he’s still in love with you?”

She nodded slowly. “I think so… I really do. And it scares me. He sounded unstable, a little crazy.” The frown deepened. “There was something else he said: ‘This is for you, Shell—for the old you, for the one who would have fought for her beliefs. No cost is too great to save the ones you love.'” She looked up at me, and her eyes were clouded with worry. “He’s up to something again. I can feel it.”

I crossed the room and took her hand in mine. “Don’t worry. I’ll be with you, this time. If he even thinks anything weird, we’ll have security straight onto him. You’ll see. It’ll be okay.”

She smiled—a little wanly, but it was a start. “I know. He won’t hurt me. It’s everybody else I’m worried about.”

Her words sent a shiver down my spine. “You think he might sabotage QDos?”

“He might. If they won’t see reason, there’s no telling what he could do. His ideals are very strong.”

I let go of her hands and paced across the room. “Christ.” An image of the world without D-mat filled my mind. The Hotel would suffer, and far more besides. The new technology had infiltrated every corner of the international market; the world would grind to a halt without it. All at the whim of one man’s impatience for environmental sanity.

Population, energy-consumption and big business: the three main targets of dB’s philosophy. He’d tried to tackle the second on the list, but the third had got in the way. What else could he do but meet QDos head-on?

Suddenly, and quite unexpectedly, I felt sorry for dB.

“Poor bastard,” I said. “What’s he going to do? Blow up all the capsules?”

“I doubt it.” Shelley stood, and came closer. “They’re not at fault. It’s the people who use them that keep messing things up.”

“Right.” I kissed her on the nose and took her into my arms. “People like us.”

“Exactly.”

My work-station buzzed, over-riding my over-ride. A party of tourists had arrived from China and needed a translator urgently. The nearest was in Brisbane and wouldn’t come unless I authorised extra incentives for the inconvenience.

Sighing, I returned to work, the matter of dB still unresolved.

#

Shortly after dinner, we walked up into the foothills of the Ranges to watch the sunset. A trail had been marked between tumbled boulders, leading upwards in a lazy spiral. The sun was balanced on the lip of the world by the time we reached the highest point of the trail. Stretched below us was the Hotel Djaralinga, arrayed like a chessboard. A haze of lights revealed a patchwork quilt of units, pools, dining halls, and shaded tennis courts. The faint electric light looked like a mist under the tremendous, yellow heavens.

For seven hundred kilometres in every direction was nothing but desert. Here, however, was life in abundance. This simple fact never failed to astonish me.

“Do you remember how we got the building permit from the Maramangidji?” I asked, and Shelley nodded, smiling.

The site wasn’t sacred; we had established this early in our bid. When the elders started talking about damage to neighbouring regions resulting from roadworks, an influx of earth-moving machinery and rapacious labourers, we offered a guarantee that there would be no incursion beyond a certain radius from the site. If there was, we would forgo all rights to the soil we inhabited and hand it back to the tribe forthwith.

We invited a representative of the tribe, a swarthy full-blood nunga named Tommy Mardjuk, to attend the site as our guest. He was diligent and suspicious, following anyone and anything that seemed even slightly outward-bound. It was a game to him, and he thought we were idiots to risk losing all on such a ridiculous wager. How could you build anything without leaving roads in your wake? Air-lifting was too expensive to an area this remote.

Two weeks after the arrival of the first mass-moving capsule, however, Tommy gave up and went home to Perth. The last we heard of him, he was selling capsules to remote outback stations. Another victory for QDos: the triumph of the bourgeoisie over tradition.

That thought reminded me of dB, and the moment of self-satisfied reflection instantly soured.

“I wish we’d had kids,” Shelley said, startling me.

“We will,” I assured her. We certainly intended to, one day. “What’s brought this on all of a sudden?”

“I don’t know. A womanly feeling, I guess.” She caught my look and punched me on the shoulder. “Not my period, you asshole.”

I went to hug her—something really was bothering her—but my intercom broke the moment again.

“Yes?” I snapped into it.

“Boss? This is Charles. Something strange is happening down here.”

A sudden chill made my arms tingle. Charles Stanton worked in the D-mat facility. Coming on the heels of the phone call that day, the thought of anything ‘strange’ happening with the Network was a discomforting coincidence.

“Like what exactly, Charles?”

The reception was poor as his reply came through. “We had a command I’ve never seen before from QDos central, rerouted through AUSSAT-4. The capsules went on automatic. It’s hard to tell exactly what’s going on in there, but they seem to be cycling data with the doors open.”

“I thought that was impossible.”

“Me too, boss.” A rising hiss rapidly drowned his words. “I don’t know…we call someone…?”

The intercom died with a puzzled squawk, and I shook it, frustrated by the breakdown in communications.

Then Shelley grabbed my arm and pointed urgently down the slope of the hill, towards the Hotel.

The D-mat complex was glowing faintly in the deepening twilight. A purple radiance washed out of the plate glass windows and across the artificial lawn. Its unearthliness reminded me of the ghost-light found in the heart of a nuclear reactor, or the glow from a UV fluourescent tube.

Shelley grunted and stepped away from me, the sound and movement coinciding exactly with a flash of intense purple from the reception building.

I turned to her. She was frowning, pale, inwardly concentrating.

“What’s wrong?” I asked.

“I don’t know.” She put her hand to her head. “I feel kind of—”

There came a second flash of light. She stopped in mid-sentence. Concerned, I put my hand on hers—and pulled it away instantly.

She was cold. As cold as marble.

I looked around for help, but we were alone. All sound from the Hotel had ceased, leaving the evening eerily silent. The only movement was the flickering glow from the open D-mat capsules. Like a statue, Shelley stood immobile before me, her face still creased by a frown.

Then the twinkling started. Tiny motes of light, no larger than specks of dust, crawled across her skin. Minute fireflies in a strange dance curled and spiralled from the crown of her head, tattooed her face, cascaded down her shoulders, arms and chest, merged into a torrent of light at her hips to waterfall down her legs. Like a bottle of sunlit champagne, she gradually filled with light, effervescent and white-gold.

It took no more than a handful of seconds for her to fill. I stepped backwards, dazzled by her radiance. She had become a nova, coldly blazing, dimming the setting sun behind her. It hurt to look at what she had become and tears streamed from my eyes, but the night seemed full of light everywhere else I looked. I began to hear a hissing noise.

“Shelley!”

The hissing became a crackling and individual motes of light started to go out, diminishing Shelley’s brightness point by point. When they went out, they vanished entirely, leaving nothing in their wake.

Shelley dissolved like a pillar of salt in the rain. Strange caves formed in her cheeks and stomach, holes opened like new mouths on her arms and legs, gaping, joining together in a spreading patchwork of cavities. She diminished quickly, becoming a framework only vaguely humanoid, a fiery web, until only a few specks remained.

Like fairy-dust, they sparkled briefly, then also disappeared.

And she was gone.

#

I don’t recall much of the next hour. When the retinal image faded, I looked down into the valley and the Hotel had gone too. Eventually, I noticed the sunburn.

Sunburn.

After years of exposure to the desert sun, my skin had become as black as a nunga’s. I haven’t been burnt for as long as I can remember. Yet, that evening, my face and hands were red-raw, alive with pain every time I wiped away the tears. My legs, too, and neck and chest. My groin ached as though on fire.

When my skin started to blister, I thought of radiation, and that in turn reminded me of the ‘loose gluons’.

Screaming impotent grief into the mocking faces of the Djaralinga Range, I tore the bracelet from my wrist and hurled it with all my strength at the stars.

#

The sun rises. The night was bad, but the day is worse. I am thirsty and hungry and I think of using the gun if I have to wait much longer. I can feel my mind shrinking as I lose moisture to evaporation. I am becoming less civilised by the hour, reduced to a creature sucking the damp from the shadows where the pump once stood.

The radio works. I recognise it as one I brought back with me after a quick trip to Rome, last year. It helps pass the time as I sit here waiting. I can hear voices from the other side of the world, shouting in fear and anger, wondering what the hell has happened.

Collapsed sky-scrapers, food and water shortages, missing loved-ones… The list goes on. One voice bewails the loss of the space stations. All gone in a blaze of light and fire, like Shelley.

“Man, it’s obvious,” says another voice with a heavy West Virginian accent. “My brother went in one of them machines last month, and he went zip along with the others. I couldn’t afford to go with him, so I’m still here. Makes sense, don’t it?”

Obvious even to the simplest layperson. If I could talk to them, I could confirm their suppositions: dB built a flaw into the D-mat system. Everything that went through it—animate or inanimate—was reconstructed incomplete, with a basic weakness, like houses of cards waiting for the wind to blow them down. At his signal, transmitted through the D-mat capsules all over the world, everything fell apart. Literally.

Except me.

He had been preparing for this moment from the very beginning. But he might never have sent that signal had QDos not halted the sixth generation. If D-mat had replaced every form of fossil-fuel transport, then dB might have been content. But QDos succumbed to the basic instinct of big business—greed—and that made dB mad enough to press the switch.

I imagine the globe awash with purple faery-light—then ablaze with the fiery death of a middle class.

England, Europe, America, Australia, Japan, Canada—how much will be left? Our affluent nations embraced D-mat whole-heartedly. There was hardly an aspect of our lives that did not include it.

Then I imagine places like Africa, Indonesia and Eastern Europe, where the poor had little or no access to the Network. Only the military used them, and the very rich. These places will be leaderless, chaotic. People are dying everywhere, and I can hear cries of pain amongst the shouts of victory.

dB is either history’s greatest murderer, or the saviour of mankind. In my water-starved state, I cannot decide which. With one stroke, he has culled a population of billions and all-but destroyed the web of business that has strangled the globe for over a century.

He has sacrificed the present in the hope of a better future—and perhaps only the future will tell whether we should thank him, or damn him.

I can only guess what Shelley would have thought. Perhaps she knew more about it than she said. Maybe that’s why she gave me the pendant.

Time evaporates in a shimmering haze, and my thoughts begin to turn with a ponderous weight, gaining momentum but going nowhere.

Far overhead, a jet flies by, leaving a streamer of white in its wake. The jet keeps going, but I can hear its distant grumbling as it turns and comes back.

I go down the side of the ridge towards the landing-strip, fingering the gun in my pocket. Exactly what I’ll do when I get there, I just don’t know.

But I guess I’ll think of something.

(Image credit: morguefire)